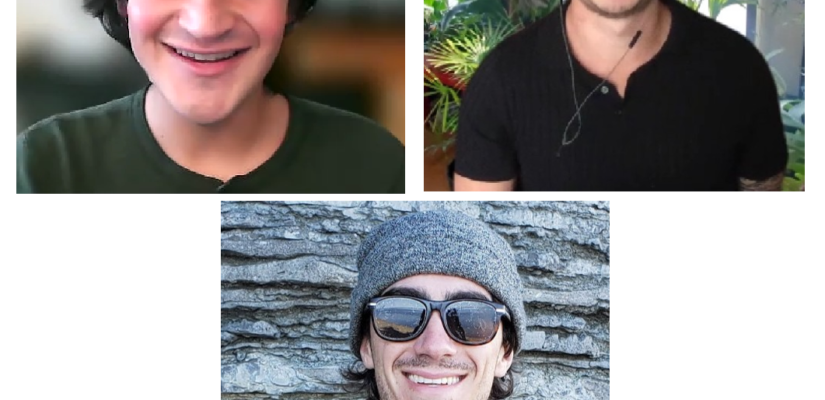

Tanner Frank, Jaemin Lee, & Joshua Zimmt: Bringing Fossils to Life, BASIS Volunteers

April 2021

Tanner Frank, Jaemin Lee & Josh Zimmt

Tanner Frank and Jaemin Lee are third year PhD candidates at Cal Berkeley in the Integrative Biology Department. Tanner studies Paleoecology and Jaemin Lee is studying evolutionary ecology, or plant and animal interactions over time. Joshua Zimmt is a 4th year PhD candidate at Cal studying with the UC Museum of Paleontology. They’ve been involved with BASIS for the past three years.

What led you to pursue a PhD in Integrative Biology?

Tanner Frank: Since I was very little I always loved being outdoors, being in nature, observing animals. I always wanted a pet but I was allergic to dogs, so that didn’t pan out for me. Once I learned to read I got really into dinosaurs and learning about all the animals and creatures that lived before the present time. So from the time I was five years old, I had the goal of becoming a paleontologist. Until I got to college and studied abroad with an ecology program in Costa Rica. For a bit I was wondering if I wanted to study interactions between organisms in modern day and conservation, but in the end I was able to fuse the two. I now study paleo ecology, which I think is the best expression of my interest in science.

Jaemin Lee: Like Tanner, I’ve been interested in nature in organisms, mostly as a hobby. I liked catching insects and raising them. I’ve been interested in the fossil record, dinosaurs, and the vast history of life throughout time. It wasn’t until I came to UC Berkeley in undergrad as a study abroad student that I learned that I could combine those, do research, and potentially have a career in this. That’s when I wanted to become a biologist that studies paleontology.

Joshua Zimmt: The catalyst for my career in paleontology happened when I got to college. I took a geology class, and the professor happened to be a paleontologist. When I heard there were fossils right off campus, I went to her and asked, “Where can I find them, where do I have to go?” Like any freshman college student on a Sunday morning, I woke up at 7am, went into the woods in the middle of Virginia. I walked past to where I was supposed to dig and ended up in a riverbed and started digging. Eventually I heard a clink and pulled a scallop that was 7 million years old right out of the riverbed. It was the first fossil I found and the first time I thought there was more to fossils than bones and dinosaurs. I started asking questions in my head, and when I learned we can answer these questions by studying the fossil record, that’s when I knew I wanted to be a paleobiologist.

Who inspired you along the way?

Tanner Frank: For me, none of my immediate family was in science, but my aunt is a huge science enthusiast and amateur astronomer. She lived in New York City and so she couldn’t see the stars, so she’d bring her telescope to our house. She’d taught me about the stars and space and it expanded from there. She helped fuel my interest in science and made me realize that it was possible to do this long term, because she expressed it was something she was interested in.

One important thing that I think BASIS is so great for is that–obviously we want as many people that are interested in being scientists to feel like that’s a possibility for them. In addition to that, I think even for people who won’t end up going into academia or being scientists, to give them a passion for science and realize that science is a useful thing is good for society and for those people.

Jaemin Lee: For me, I’ve been interested in organisms and growing them, like a horticulturalist. But, it wasn’t until fourth grade when my homeroom teacher recommended me to a special science education program. She saw me looking at plants during every break in class. That transformed me: I got exposed to other forms of science and I started to make links between what I see and understand. Finally I started having answers to things I had been wondering since I was young.

That was transformational and I wish I could do the same thing through my teaching at Berkeley or through BASIS. It’s great that we can talk about science, excite people, and make them realize it’s a career they can also pursue.

Joshua Zimmt: My biggest inspiration was my undergraduate research advisor. She pushed me not only to ask questions but encouraged me to take really big leaps in my research and in life. Part of the reason why I am a scientist today is because of her mentorship and guidance. My work with students of all ages and backgrounds is to ask the questions that interest them most and to inspire them to pursue these questions and take risks to find something about the world around them.

What brings you a sense of wonder in your work? How do you create wonder for others?

Tanner Frank: One thing that always helps me restore that sense of wonder is going out in nature. Going to the ocean and observing animals always does that for me. I got a pet snake and watching her do snake things–realizing there’s a life outside of people. That sense of connection with things that seem unrelated and science helps reveal how those things are connected, whether through evolutionary relationships or ecology, throughout the whole universe. In my research I study food webs and I think that’s our crude human way of trying to capture some of those connections between organisms. I’m interested in helping to develop that part of ecology.

Jaemin Lee: Wonder feels like a distant word. To me it’s similar to curiosity which is a big part of science. It’s an everyday thing, if you walk around and see a plant and think, “Why is this insect with this plant and not this one?” The same thing happens in the fossil record, we just don’t have a complete picture of it. We have to figure out if a plant from this locality or that locality were from the same group or a different group. It’s about questioning everything we see. That’s why the BASIS program inspires me a lot because you see a lot of students asking us questions. I feel as people get older when they ask questions they say “This might be a stupid question” but it’s like everyone says, there are no stupid questions. I like that about how these students are making questions, asking stuff that they found interesting throughout the BASIS lesson.

Joshua Zimmt: A continuous sense of wonder for me is the vastness of the history of life on our planet. There’s so much that’s happened over the planet’s 4.6 billion year history and for 3.5 billion years we have fossils to study and things to learn. There’s so much left to learn that I can’t help myself from wondering about what we might discover one day. For me the wonder is captured in the fossils, that you can pick up something and it can be 450 million years old. I try to bring this into all the work I do. You give someone a fossil, they think, “Oh, it’s just a fossil.” Then you ask them how old it was, and what they think it was. As they learn more about it the wonder grows, because then you realize it’s not a rock, it’s actually something that was once alive that we can look at today millions of years later. It can unlock a whole new world of questions for those students.

Describe a discovery that you’ve made.

Joshua Zimmt: My most interesting discovery was an unexpected one. I study how the rock record affects our interpretation of the fossil record. I didn’t expect to find much by way of fossils at my field site, in Anticosti Island in the subarctic of Canada. This is a place that’s been studied in the last 150 years. It’s been combed over by paleontologists for so long. And yet I was still able to discover four new species on the island over the course of my work. It led me to realize how much we have left to learn.

Jaemin Lee: One of the privileges that scientists can have is that they will know something for the first time that others don’t know until they publish that work or go to a conference, until they share that information with the general public. You get to know something for the first time in the world that nobody else knows. That kind of thing is very fascinating. What I’m currently working on is Jurassic period flora from California and Oregon. This is a time before all the flowering plants we see were even present, so the composition of plants are totally different. Compared to the modern day, in the continental US there aren’t that many “exotic species.” For instance, ginkgo– the only living species is ginkgo biloba, which is from China. Back in the time of the Jurassic [period] California used to be covered with these ginkgos that were growing naturally together while the dinosaurs were still roaming the continent. That was interesting to see because it’s non-analogous, there are no comparable landscapes in any modern ecosystem that are remotely similar to those.

Tanner Frank: It is a privilege to work on questions that I’m interested in for a career. Right now I’m working on these fossils that are microscopic, in shales. Rocks that are 385 million years old, before the dinosaurs, when life was first getting onto land. I’ve been dissolving rocks in acid and then you go through the microscope and look for them. Fossil shells, shrimp like organisms, organisms that were around hundreds of millions of years ago that nobody has ever seen. It’s awesome for that to be my day job, and it’s nice to take a step back and appreciate how cool the things you’re looking at are.

That’s also one of the great things about BASIS. We talk to kids and they think that fossils are cool, it reinvigorates my own sense of wonder.

Describe a goal you have.

Joshua Zimmt: To teach students that science is a process of inquiry. It’s not a series of facts, we’re always learning new things. Some of the questions they might be asking could lead to a new discovery down the road. They could be a scientist if they start asking the questions.

Tanner Frank: Every class the students are enthusiastic, but there’s always a few students in every class who aren’t responsive and answering all the questions. The best for me is as the lesson goes, they start to ask questions and start to get more interested. For me it means that you got someone interested in something that they wouldn’t have thought they were interested in before.

Extra Footage: